Beneath the Surface is a monthly column by Robert Lim that examines the cultural side of heritage fashions.

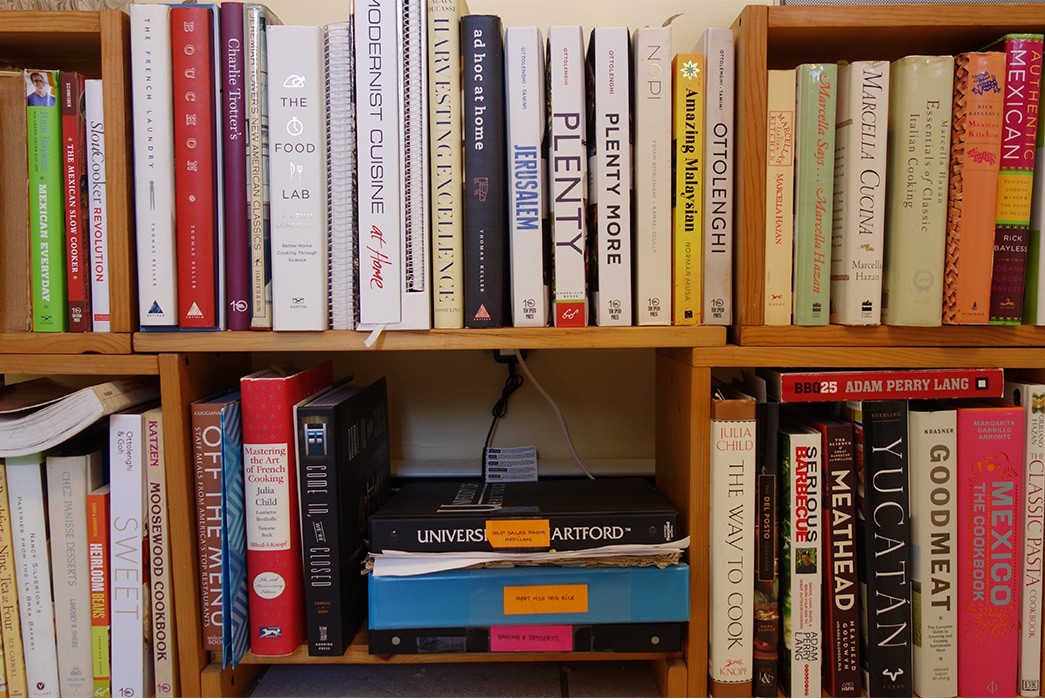

I have no idea how other people spend extended holiday time off away from work, but I use it to take on cooking projects. Most recently, I made a French stew (daube) from a beef “osso buco” shank cut I bought at a proper butcher shop in Manhattan. I initially used a recipe from Julia Child’s Mastering the Art of French Cooking, over a traditional base of egg noodles. It yielded a ton of leftovers, so the next day I used instructions from another cookbook to make a more refined version that would have been cutting edge in the ’80s.

I suppose that’s because the cookbook was written by Jeremiah Tower, one of America’s first celebrity chefs – he made Chez Panisse famous (along with Alice Waters) and his story is ably told in last year’s documentary, The Last Magnificent. In a nod to those rule-bending times in California, this was served over jasmine rice, whose sweet, nutty fragrance proved an excellent accompaniment.

The base of the daube was made two days before all of this – when I make prime rib (a family holiday tradition), the roast sits on its bones while cooking, but they are detached before carving. These parts make for a splendid broth, along with the various chicken backs and offal that accumulate in the freezer of someone who hates food waste. The rest of this broth will be used later, in the manner of the Italian region of Emilia-Romagna, as a rich, simple backdrop for handmade egg tortellini. Bone broth is a thing these days, but what the Italians call “brodo” has been around forever.

Fig.2 – Daube v. 1

Home cooking is something that I’ve been doing for more than two decades – quite simply, it’s one of the only useful skills I have. My day job is oriented around long-term goals (with outcomes that are tricky to measure), and most of my past-times aren’t productive in the traditional sense. So, it’s rewarding to start with raw ingredients and end up with food on the table – a tangible product of my efforts. And it comes in handy, given the limited choice in quality dining options where I live (even more limited, if you don’t feel like having a hamburger or pizza).

It wasn’t always this way – as with any useful skill, it took a long journey of deliberate, intentional practice, with an equally lengthy trail of missteps and the occasional disaster. One of my first early cooking inspirations was a college roommate’s copy of Marcella Hazan’s 1973 landmark The Classic Italian Cook Book, and after helping him make a successful version of fettucine alfredo, I got it in my head to take on gnocchi.

Making gnocchi is simple, and I figured it’d take an hour. And that might have been possible – if I had my mise en place properly set. My inexperience forgot to account for such things as: the time it takes for water to come to a boil, the time it takes to peel potatoes (and maybe that you could do those two things at the same time), and hey, isn’t there supposed to be some kind of sauce? Before I knew it, I was waking one of my diners up to enjoy our 8pm meal – at 11pm.

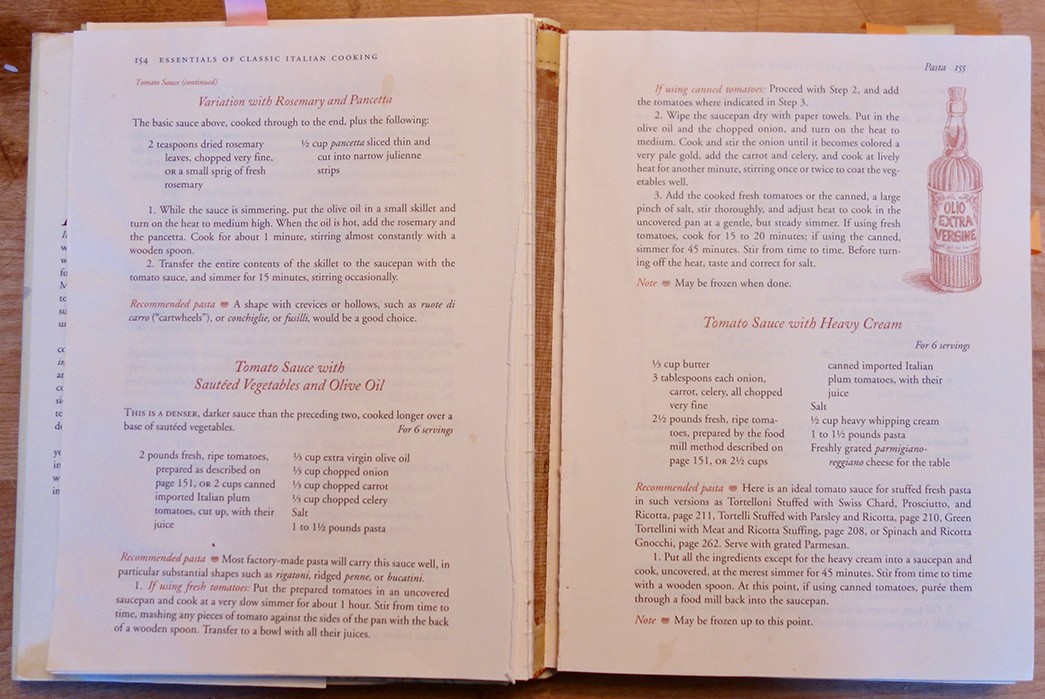

Fig. 3 – Well-worn copy of Essentials of Classic Italian Cooking – the binding has broken between two classics – a simple tomato sauce based on a soffrito, and pesto Genovese

Things started to get better a few years later. After I moved to New York City, I bought my own copy of Hazan’s book (compiled into Essentials of Classic Italian Cooking) and was soon cooking weekly out of a kitchen so small you could barely extend both arms and twirl once without touching the walls. This endeavor of betterment was handily abetted by my wife’s graduate student colleagues – she had an early evening seminar, and we became the afterparty. Something about free, decent food helped to alleviate any uncertainties about when dinner was actually going to be served. For me, it became a weekly workshop to try, fail, and try, try again.

I occasionally expanded this concept to larger dinner parties; one particularly memorable one involving seared lamb rib chops. If you’re familiar with the small scale of city apartments, you’ll know how kitchen smoke can quickly envelop the entire place. From my place at the stove, I looked out to my dining room and saw my guests fanning the doors on either end of the room in syncopation to move smoke out into the cool night air – true New Yorkers, one and all. This may or may not have been the night when someone sent back a piece of lamb for being too rare (it wasn’t able to bleat, but only just).

Fig.4 – Example mise en place, with toasted almonds and spice grinder ready to go

Over time (years and years), I got better – I learned the value of getting all the ingredients ready and in a state you can use them (the very definition of mise en place), and got much better at both multi-tasking and timing. These allowed me to take on more ambitious projects that reflected what I wanted to be eating, the ones in a gorgeously photographed cookbook, with a half page recipe that calls for three other things that you were supposed to have made beforehand. They require a little bit more patience, a lot more planning, and a chest freezer doesn’t hurt either. If you have all these things, the sky’s the limit.

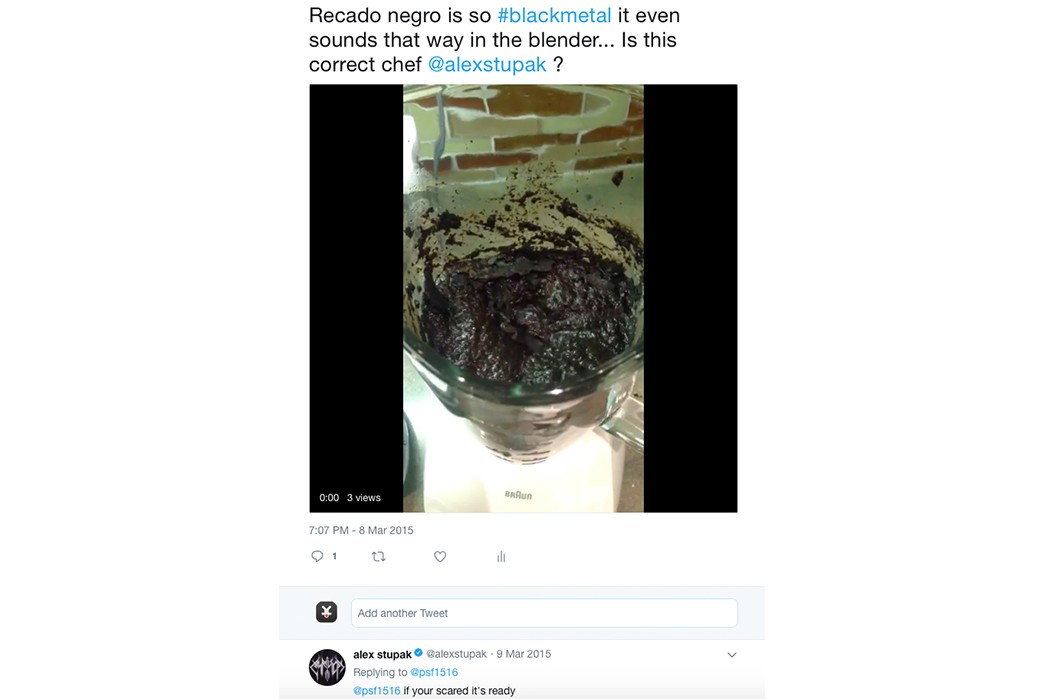

I’m obsessed with the food of the Yucatán, a region of Mexico whose food goes back to the Mayans and subsequently informed by Spanish conquistadors and Lebanese immigrants. It’s intensely laborious to make, and based on seasoning pastes called recados (the Yucatán version of the more famous moles). If you lived there, you would likely buy it pre-made at a market, but a home cook in Connecticut has to do it himself.

So, for a pitch-black, ashy, recado negro (which is so ancient, it has been called the ur-mole), I’m making a recado rojo to incorporate in, toasting spices, charring garlic and onion, and roasting chile peppers until they look completely burnt and ruined. And that’s just step zero to any actual dish. Why so much effort? Food this complex is built from layers of flavor; the final dish has a complexity matching its preparation, and is packed with taste sensations that you may never have known existed. And all of that takes work.

Fig. 5 – Making a Recado Negro (and making sure it’s right) – link to video here.

Most importantly, along with being able to take on more complicated recipes, I learned how to call audibles when the recipe was starting to go sideways. This is particularly important when dealing with meat and other proteins – animals are different from one another (size and fat content, to name two significant variations) and their meat, usually butchered without your input, will respond differently. Being able to figure out when something needs a different approach can be the difference between throwing away hours of hard work and having something presentable to your guests.

And sometimes the recipe will just be off, such as a recent one I’ve come across that calls for simmering cubed boneless leg of lamb in a sauce for thirty minutes until it reduces. Leg of lamb is a lean cut, so if you simmer it that long you’ll end up with small, unchewable protein pellets. I put in a quick fix (simmer for ten minutes, reserve and season meat while you reduce the sauce; recombine and warm at end) and soon I was enjoying a wonderfully complex kerutup kambing (lamb curry from Kelantan, on the east coast of Malaysia). A longer fix might involve the use of lamb shanks and a long simmer with the lid ajar.

This journey can be summed up in my other holiday cooking project this December – the so-called “100 layer lasagne” from Mark Ladner’s Del Posto cookbook. I first noticed Mark Ladner during his days at Lupa, which he opened in 1999 after serving as sous chef at Babbo. It was reliably delicious, relatively inexpensive, and featured memorable specials. I still remember: simple pastas with ramps during that brief moment in spring when farmers’ markets are flooded with them; a fresh porcini mushroom “salad” served at a fall lunch; a porchetta from a suckling pig that is still one of my ten best meals in New York City, fifteen years later. Ladner went on to open Del Posto, where this lasagna became a favorite on his menu. So when he published his Del Posto cookbook last year (shortly before hanging up his apron to start a gluten-free fast casual project called Pasta Flyer), I was all over it.

Fig. 6 – Lasagna, one layer at a time

Making lasagna from scratch is time consuming, mostly because of the number of elements. You need a filling (traditionally a meat ragu), a bechamel, and of course you have to make the pasta (one thing I’ve internalized from Marcella Hazan – pasta dishes are about the pasta, not the sauce; so a lasagna without a homemade pasta might be tasty, but it isn’t a proper lasagna). To this trinity, Ladner’s version adds a separate tomato sauce, which is basically a simple tomato sauce reduced into concentrated, tomato-y essence. The lasagna is assembled and chilled overnight, and on the day it is served, it is portioned and fried (to emulate the sweetly crisp goodness of the edge pieces in a more traditional lasagne). The whole thing is served on a bed of the tomato sauce, which cuts into the deep richness of the lasagna.

Happily some of this can be made in advance, so the whole thing can be spread out over three days (bear in mind, this is a simplified version of what the restaurant served):

Day 1: sauce and ragu

Day 2: pasta, bechamel, assembly

Day 3: portion, finish and serve

The sauce was easy, and the key to the ragu is to keep it at the barest of simmers to make sure the ground meat doesn’t dry out. A slight mistake (pouring in a cup of milk instead of a quarter cup) was easily remediated by simmering longer (another Marcella tip: you know when it’s cooked down properly when dragging a wooden spoon through the bottom of the pan is not immediately followed by liquid rushing into the path your spoon just made). I’ve never liked making bechamel (you make it by cooking flour and butter together, adding milk, then reducing it), because it takes forever to reduce. I chose a wide saute pan to maximize evaporation through air contact, and it was easy and painless.

The pasta presented a different conundrum – the recipe calls for two types of flour: a special Italian flour that’s been ground so fine it achieves a pillowy softness (called “00,” or doppio zero for “double zero”), and a durum flour, which is basically semolina that’s been ground to a flour-like consistency (instead of the sandy consistency of semolina). I’ve been saving “00” in the pantry, but couldn’t find any durum. What I ended up doing was taking the finest semolina I could find and processing it in a food processor for fifteen minutes. I have no idea if it made much of a difference, but the end result worked, so I’ll take the W.

Fig. 7 – Frying lasagna al Posto

Assembly was fun with someone else to provide company (and an extra pair of hands), and the portioning yielded a nice surprise – you trim the edges of the lasagna for presentation (and to create a nice flat surface for frying), which gives you about two portions of scraps. And if frying one side is good, frying the scraps gives you more char per ounce – a little cook’s treat for later. Finishing the lasagna proper took fifteen minutes – a simple salad and a nice, twenty year-old bottle of Ruche from Scarpa proved the ideal accompaniment for a festive occasion.

The benefit of an easy Day 3 is that you’re not so exhausted you can’t enjoy the meal; it was a wonderful start to the New Year on a quiet family evening. And, reflecting on the process of this one – sure there were a lot of steps, but each one was simple and containable; for all the grandness of the final product, Ladner clearly took effort to make the steps, familiar to me over decades of cooking from Marcella, easy to follow. And each minor course correction and decision was informed by years of trial and error, internalized learning and experimenting.

Fig. 8 – Final plating

I’m sure a lot of you are thinking – that’s cool, but it sounds like a lot of work – I’m busy and there sure are a lot of great restaurants near me. So why go through all the effort?

First off – I was lucky to grow up in a household where home cooking was the norm. Beyond the practicality of putting food on the table, there is something demonstrative about putting effort into nourishing someone you love. Quite simply, it’s the difference between saying you love them, and showing that you love them.

Secondly – as you can probably tell, I take great pride in what I do. And things I do try to do, I try to do well. Every time I take on a new dish, I get to push myself a bit to do something new – using skills I’ve developed over the years. Being able to consistently bring that to the table, and experiencing it for the first time with friends and family, is priceless.

This is the part of the year where many are making resolutions for the New Year. Whether or not you believe in such things, I hope people consider trying to get better at creating things. At Heddels, we write all the time about craftspeople who pour their passion into products we admire, covet, and (sometimes) wear. They love what they do, and we are better for their efforts – which were themselves honed over years, if not decades, of experience. So this year, I’m hoping you will find time to spend time on such an endeavor near and dear to your heart – a skill that takes minutes to learn, but a lifetime to master. And I’m also hopeful you are surrounded by people who will support you when you screw up. It’s those long journeys, accompanied by lifelong friends, that end up being so satisfying, that give our lives meaning.

This column is dedicated to my mother – such are her standards, I knew I was onto something when she started to allow me to cook with her in her kitchen.

More Reading

If you’re interested in getting better at cooking, here are some personal recommendations suitable for all skill levels.

If you’re just starting out:

These sites spend a lot of time developing foolproof recipes in test kitchens, and just as much care to explain why they’re doing what they’re doing. You get training wheels and safety rails, and the results are all but guaranteed to be delicious:

- Serious Eats – The site’s Chief Culinary Consultant, J. Kenji López-Alt, has also published the encyclopedic The Food Lab (Norton, 2015)

- Cook’s Illustrated – The definitive site for everything from how to make chocolate chip cookies to roasting a Thanksgiving turkey. Their methodology may be quite prescriptive and pedantic, but follow it to the letter and you really can’t go wrong.

- Amazing Ribs – Honorary Mention edited (and mostly written by) “Meathead” Goldwyn – he’s published a cookbook, Meathead (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016) – it has both easy-to-follow recipes and also copious notes about the science behind barbecue, which can be translated to great results on your own backyard grill.

If you want to explore new boundaries:

Marcella Hazan, Marcella Cucina (Harper Collins, 1997) as much as I love the Essentials of Classic Italian Cooking, this is her most creative book and the one most suitable to the modern American palate. $26 at Amazon.

Rick Bayless, Mexican Kitchen (Scribner, 1996) – back when there were almost no good Mexican restaurants in the Northeastern US, this cookbook introduced me to the kaleidoscopic world of regional Mexican cuisines in a fairly approachable manner. $20 at Amazon.

Yotam Ottolenghi and Sami Tamimi, Jerusalem (Ten Speed Press, 2012) – Ottolenghi has introduced Middle Eastern fare in a cosmopolitan and surprisingly easily accessible way, in one of the great cookbooks of this century. This is also an essential starting point if you’re interested in a flavor-packed plant-based diet. $27.50 at Amazon.

If you’re an experience home cook and have a long weekend:

Adam Perry Lang, Serious Barbecue (Hyperion, 2009) – while barbecue lives in the rural South, every summer affords us backyard grillers the opportunity to make some serious, A-list barbecue. This book is packed with tons of techniques that layer on flavor. If pork is your only meat that matters, treat yourself sometime to his recipe for St. Louis ribs. $26.50 at Amazon.

Thomas Keller, Ad Hoc at Home (Artisan, 2009) – Chef Keller applies some of his continental training to home-style American cooking. I’m not a huge fan of over-the-top fine dining experiences, but applying that technique to casual food is an eye-opener. People travel to this restaurant on Mondays for their fried chicken – make it at home and you’ll be spoiled for anything else. $32.50 at Amazon.

David Sterling, Yucatán: Recipes from a Culinary Expedition (University of Texas Press, 2014) – Half travelogue and cultural anthropology, and half an incredibly detailed exploration of the food of the Yucatan. Mexican food is as diverse and sophisticated as Chinese food, and this is the deepest dive I’ve seen anyone take on any of its regional cuisines. This may end up being the most labor-intensive cookbook you’ll ever own, but the efforts are worth it. $41 at Amazon.