When I first began to learn about the history of Japanese clothing, it was on discussion forums and message boards like SuperFuture and Style Forum. Precious few people on there actually knew what they were talking about but that only emboldened many users’ determination. The communal nature of how western denimheads sought out the stories behind their favorite brands was exciting, many people brought together tiny pieces of information to form a decent picture of what had happened.

What was lacking, however, was one unified voice to bring all this information together–to track down and verify all these errant leads, and ultimately craft the whole thing into a narrative that could be understood as a whole. It was lacking until last December, when W. David Marx’s book Ametora: How Japan Saved American Style hit the shelves.

In just under 300 pages, Marx follows Japan’s men’s fashion scene from rough interpretations of American Ivy to artisanal reproductions of American denim to high concept streetwear brands like A Bathing Ape. Not only does it explain the fashion scene, but it also serves as a synecdoche to greater understand the development of post-war Japan for historians of all stripes.

We had the pleasure of talking to (as well as working with) the author about his project and his thoughts on Japanese fashions today.

Heddels: What prompted your interest in the interplay between Japanese and American fashions?

W. David Marx: I first went to Tokyo in 1998, and at the time, I was very into the Japanese musician Cornelius. So I was flipping through a magazine one day and saw a T-shirt with an ape head from Planet of the Apes, which came from a brand called A Bathing Ape. The next day I went to the store and spent literally three hours waiting in line to buy a shirt. And then I went up the street and saw resellers selling Bape T-shirts for double the price. This made me realize that something very different was going on with fashion in Japan, and I ended up doing my senior thesis on why A Bathing Ape’s “anti-marketing” (hidden stores, undersupply of product, no ads, etc.) worked so well.

Planet of the Apes themed tees from A Bathing Ape. Images via Yahoo Japan.

After moving to Japan 12 years ago, I would casually read about the history of Japanese fashion, but I decided to start working on Ametora around 2010 when Take Ivy came out in the U.S. I ended up meeting one of the Take Ivy authors, Shōsuke Ishizu, and from talking to him realized there was an amazing story behind American fashion coming to Japan that no one had told yet.

An Image from the 1965 book, “Take Ivy”, a project of several Japanese fashion editors to document what American Ivy League students wore to class. Image via New Yorker.

A lot of people assume that the story would be very simple: “Japan loves America, therefore Japanese people wear American clothes,” but the history is more complex and fascinating.

What does “Ametora” mean? Where and how did the term develop?

The Japanese language often shortens long foreign words into four syllable abbreviations, so “American traditional” (amerikan toradishonaru) got shortened into ametora.

The term originally meant the clothing of the East Coast establishment, but I think we should broaden the term to mean any Japanese adaptation of traditional American styles. I think jeans, rustic Western clothing, rock’n’roll, and hip-hop are just as important to America as style traditions as what Ivy League students were wearing in the 1960s.

Most of the information I had on the subject before reading the book was hearsay and speculation at best. How did you begin researching the book and was it difficult to verify your facts?

There is not really one Japanese book that covers the whole of what I cover in Ametora, but there are many good books on most of the topics like Van Jacket, denim, Heavy Duty, motorcycle gangs, etc. (The history of the vintage buyers in the U.S., however, is conspicuously undocumented.) Most of the individuals in the book, like Kensuke Ishizu or Yasuhiko Kobayashi, either wrote their own autobiographies or did oral histories with other journalists. I read all those, so by the time I interviewed subjects directly I already knew most of their stories and could dig deeper.

A vintage ad for VAN Jacket and an issue of Japanese men’s magazine, Heibon Punch. Images via Twitter and Heibon Punch

I also used the National Diet Library to look up a lot of old Japanese magazines and see how people felt about things back in the day. Those magazines helped me discover a lot of things haven’t really been written about in Japanese. For example, I found what is likely the first use of the pejorative term yankii for working-class Japanese youth in an issue of Heibon Punch Deluxe from 1966.

I wanted to be extra careful about verifying facts, so I would cross-check all the different accounts against each other and demand extraordinary proof of extraordinary facts. For example, I wondered for a while whether police really arrested Ivy League-dressed teens off the streets of Ginza in 1964, but I was able to find the original newspaper reports and the photos.

Do you think the Japanese obsession with American Ivy and workwear styles is a direct reflection of American occupation and reconstruction post WWII? Would they have had a similar fascination with say Russian styles had the USSR had won in Japan before the United States?

A Soviet bloc Japan probably would have had its own issues around freedom of dress, but the important thing to understand about the U.S. Occupation is that it did not have much direct impact on how Japanese men dressed for two full decades. A lot of rebellious kids and gangsters picked up American styles, but white collar men continued to dress in tailored British-style suits and students wore black wool square-collared, Prussian-looking uniforms. It wasn’t until Kensuke Ishizu of VAN Jacket brought Ivy League fashion to Japan in the early 1960s as an intentional business venture that kids started dressing like Americans. And this wasn’t necessarily imitated from Americans at the time but filtered through VAN Jacket’s somewhat limited understanding of classic campus style.

Kensuke Ishizu, the founder of VAN Jacket in 1955. Image via Lapham’s Quarterly.

That being said, Japan being a part of the American political sphere meant that youth saw a lot of American movies and TV which gave them aspirations towards an American lifestyle. People talk about the wonder of seeing American refrigerators filled with foods. But after a while this idea of “America” detached from the actual United States.

And also, American style wasn’t always about imitating America. Take the “regent” hairstyle which looks like an Elvis pompadour but has represented defiance in Japan since the 1930s. And there were many times when teens intentionally rejected American looks, either because they were seen as a symbol of the U.S. military aggression in Asia or because Europe represented a higher, more wealthy culture.

How have currency fluctuations, especially recently, affected the relationship between Japanese and American fashion?

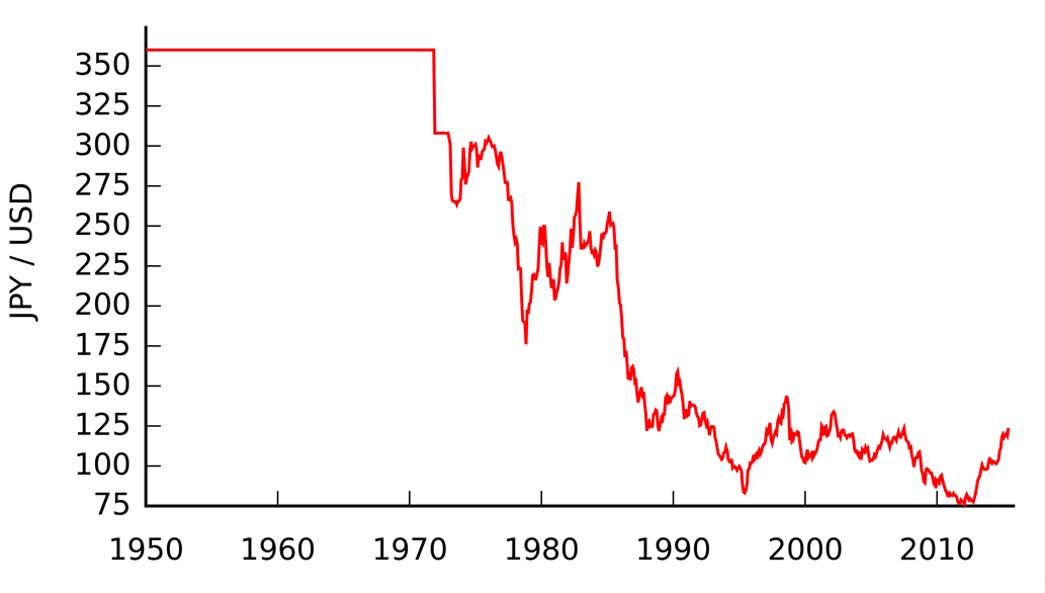

The big change came in the late 1970s when the yen became strong enough to import actual clothing from the United States. In the 1960s when it was the ridiculously low 360 yen to a dollar, no one could afford to buy anything from abroad. The guys who wrote Take Ivy said they went to Brooks Brothers and J. Press on their trip but could not afford to buy anything. But by the end of the 1970s, the yen had gone under 200, and then in the early 1990s, it dropped under 100.

The Japanese Yen versus the US Dollar. Image via Wikipedia.

The big boom for American casual came directly from the fact that the yen was so strong anyone could get a cheap ticket to the U.S., raid outlet stores at full retail prices, bring back stock in their luggage, and then sell everything for double the price in Shibuya. These days the yen is cheap again which may be helping Japanese brands export at prices Americans are actually willing to pay.

A later chapter in the book examines the massive export of American vintage clothing to Japan in the 80s. How much clothing do you estimate was shipped over? Do you think that with a weak yen and newfound interest in vintage workwear that the United States might be seeing a lot of it come back?

There were two movements at the time: expert hunters going around looking for rare deadstock items and then second-hand stores just buying up huge shipping containers of used clothing directly from rag houses. The latter stuff is not really valuable. I don’t think anyone from the U.S. is going to want back a bunch of old 1980s gym shirts from Kansas high-schools.

Americans could easily buy back all the rare vintage stuff…if they’re willing to pay for it. A lot of it is just sitting out for sale in Tokyo vintage stores like Berberjin. But as far as I know, the Japanese collectors are still outbidding Americans for most of the rare items coming into market. Levi’s seems to be getting more aggressive about buying up archive though.

Inside vintage store Fake Alpha in Tokyo.

Much of your book details the rise of American fashions in Japan via men’s style magazines that codified the “rules” of American dress. Many of those magazines like Clutch, Lightning, and Free & Easy have cult followings now of Americans that can’t even read them. Were and are English language magazines revered in the same way in Japan?

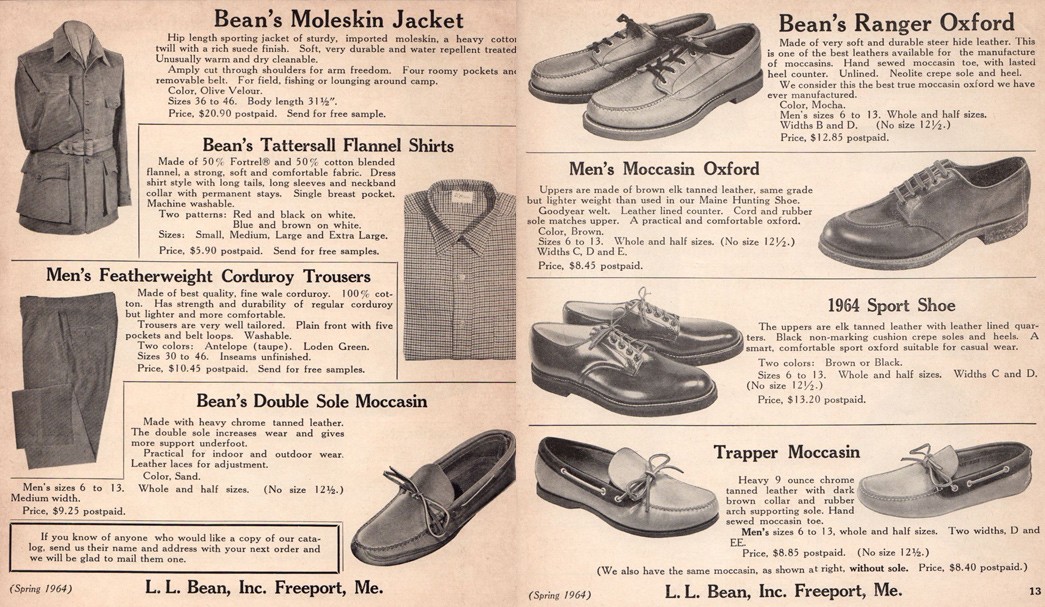

Yes, definitely in the 1960s. The guys who brought Ivy League fashion to Japan used to read through GQ, Esquire, Men’s Wear, Sports Illustrated, and the French magazine Adam. They also loved J.C. Penney and Sears Roebuck catalogs. The 1970s guys who brought in the Heavy Duty outdoor look loved L.L.Bean catalogs and did the publication Made in U.S.A. in homage to that and the Whole Earth Catalog.

Images from a 1964 L.L.Bean catalog.

In recent days, however, there are so many good Japanese magazines in Japan that I don’t think anyone really reads American magazines in a serious way. Why struggle through the English in 20 GQ pages on fashion when you can buy a 400 page Japanese magazine just on vintage menswear?

Japanese streetwear style features some of the most avant garde and unusual fits of anywhere in the world and, in my experience, it is very normalized and acceptable. Yet the introduction of your book recalls how the police literally rounded up hundreds of teenagers dressed in the Ivy style before the 1964 Olympics in Tokyo. What do you think led to the relaxation around clothing styles, or more that the way you dress doesn’t necessarily reflect who you are?

For the first two decades of the postwar, dressing out of uniform was a sign of delinquency. Ivy was the first style that changed people’s perceptions because it was sold in proper stores with advertisements and connections to celebrities. And after Ivy got big, parents watched their children get good jobs even if they dressed “strangely” during high school and college. That calmed everyone down. The compromise became, do whatever you want, just clean up and put on a suit to get a real job.

Who do you think is most directly responsible for the popularization of reproduction vintage denim in Japan? Who is responsible for bringing that trend outside of Japan to the rest of the world?

The first thing to understand is that Japan only started denim production in the early 1970s, and it was all done on high-tech Sulzer looms. So there was no real tradition in Japan of making denim on selvedge looms. In 1980, the guy running Big John at the time had a crazy idea to make a replica of vintage American jeans, including selvedge denim. He provided Kurabō with an old selvedge loom used for making sailcloth (which was a big industry in Kojima, Okayama).

These jeans did terribly, and Kurabō forgot about making selvedge denim and focused instead on mura-ito slubby denim yarns which they started selling to French brands. The next Japanese brand to start up and continuously make vintage denim in Japan was Studio D’Artisan. They did not do particularly well either at first, but kicked off the whole movement.

Studio D’Artisan’s still produced DO1 jean. Image via Studio D’Artisan.

All of this would have stayed in Japan for a long time if it weren’t for Evisu signing a deal with a British businessman in Hong Kong to start exporting to the U.K. From there, people in the West started to hear about Japanese making jeans “more authentic” than American jeans.

Also good to remember that Levi’s Japan came up with the idea of Levi’s Vintage Clothing, which is probably one of the major drivers for vintage denim styles today.

Some of the most sought after vintage and repro items in Japan are American WWII-era military wear. Is there any irony in the Japanese obsession with the uniforms of their one-time enemy or is the appreciation completely earnest?

This is a very complicated issue. First you have to understand that the military reproduction movement did not manifest inside the Japanese fashion industry but more among middle-aged men collector types and military obsessives. There are a few theories for why some Japanese men want to wear American military jackets, often ones from an era when Americans were literally bombing Japan. The two that seem most plausible are: (1) collecting Japanese military paraphernalia is taboo so people interested in “the military” have to shift their interest to American military items (2) American military items are nostalgia for the Occupation, a period in Japanese history.

A Buzz Rickson’s A2 Flying Jacket. Image via Rakuten.

I was just in Beams Women, however, and they were selling a Buzz Rickson’s flight jacket cut into a tiny size for women to wear fashionably, so at this point with “military jackets” in style, it’s all jumbled.

You mentioned that there was quite a few interesting topics that simply couldn’t fit in the finished book, any of those you’d like to touch on here?

Yes, I had to cut about one-third of the book for length. There were a few topics that definitely needed a trim: You could probably write an entire book just on VAN Jacket’s bankruptcy but it would be really boring.

A few fun things got cut though. One was an insane road trip that VAN Jacket sponsored in 1961 where Kensuke Ishizu’s second son Yūsuke drove the family’s tiny Mazda R360 coupé all the way across the United States to get a few photos of campus style. Kind of a proto-Take Ivy.

More importantly for Heddels readers, I ended up meeting a few people responsible for the beginnings of denim production in Japan — like the first guys responsible for making selvedge denim — and I hope to provide more on that soon.

We’re looking forward to it. Thanks for your time.

You can find Ametora at select bookstores and at Amazon for $27.99. W. David Marx’s article detailing the first pair of Japanese made jeans is available on our site here.