Some archeologists and art historians claim that pure artistic expression cannot exist among non-literate peoples. But when looking at Navajo arts and crafts, however, nothing seems further from the truth.

For more than five centuries, the lifestyle of the Navajo people have both amazed and intimidated the people living around them. And all the while, those people have pined after the Navajo’s crafts and desired their skills. The designs and patterns have inspired textile industries and modern fashion houses all over the world, although the high standards of traditional Navajo weaving have never truly been replicated by anyone but the originators.

That weaving tells the story of their belief, lifestyle, and the encounter with a rapidly changing world—where they were fighting subjugation, conforming with society and, with help from tradesmen, making the most of an expanding commercial market.

Native American-inspired patterns on this modern blanket from Pendleton Woolen Mills. Image via Ruby Plus George.

Navajo inspiration on the runway for British fashion brand KTZ during London Fashion Week 2015. Image via Google.

Since the late nineteenth century, Navajo rugs have started to find their way into Western civilization, and today they adorn homes all over the world. But the Navajo didn’t always make rugs—traditionally they produced blankets for wearing. It was actually a lucky coincidence, with competition and trends shaping the market, that drove the Navajo into the business of home decoration.

Navajo Culture

The Navajo people are one of the two largest federally recognized tribes in the US. They inhabited the Southwest sometime in the fifteenth century, and eventually settled down in the Four Corners region by the sixteenth century.

Not to be confused with other Native American tribes such as Apache, Pueblo or Ute, the Navajo peoples have their own language, religion and way of life. According to Navajo tradition, they were taught to weave by two holy ones: Spider Man and Spider Woman. The legend says that Spider Man created the loom of sunshine, lightning and rain, while Spider Woman taught the Navajo how to weave it.

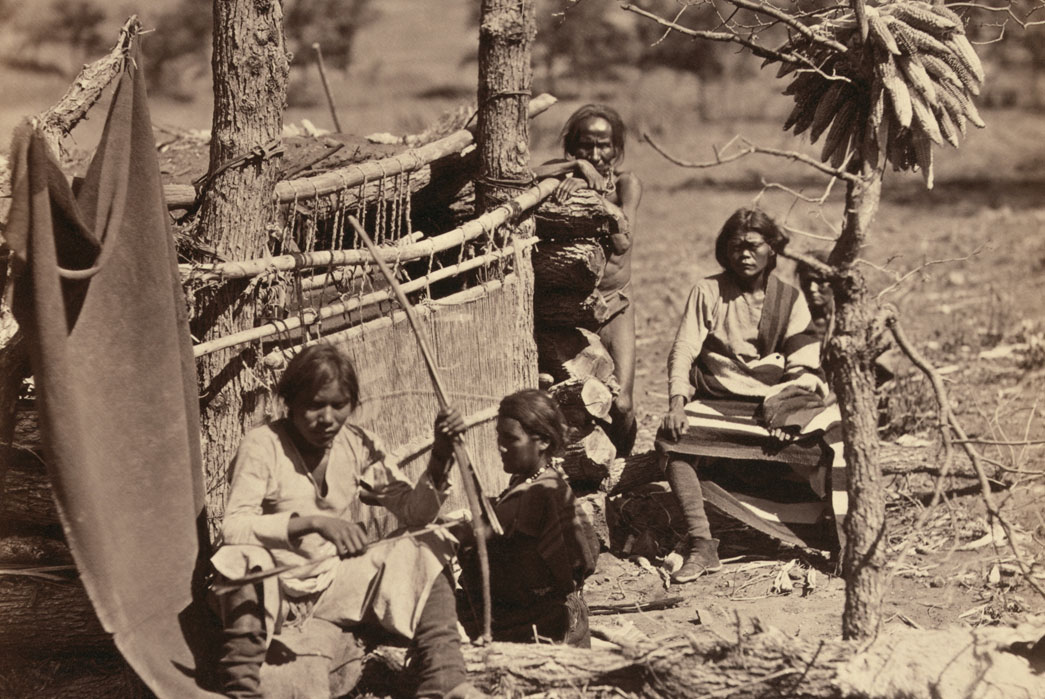

Navajo woman using a vertical, or upright loom. Image via Wikipedia.

Historically, they picked up the skill of weaving sometime in the seventeenth century. Although scholars speculate that the Navajo picked up the skill from the neighboring Pueblo tribe, the Navajo people eventually came to be recognized as the most skillful of all the Native American weavers, dexterously crafting pieces prized for their vivid patterns, durability and all-around practicality.

The Navajo people believed that no one was perfect but God, and thus what they created needed to have some degree of imperfection, a sort of humility. The Navajo also believed that they wove their soul into the pieces they created, so they’d implement a loose thread somewhere into their blankets. Invisible to the naked eye, the loose thread would allow their soul to escape.

Pueblo Influence

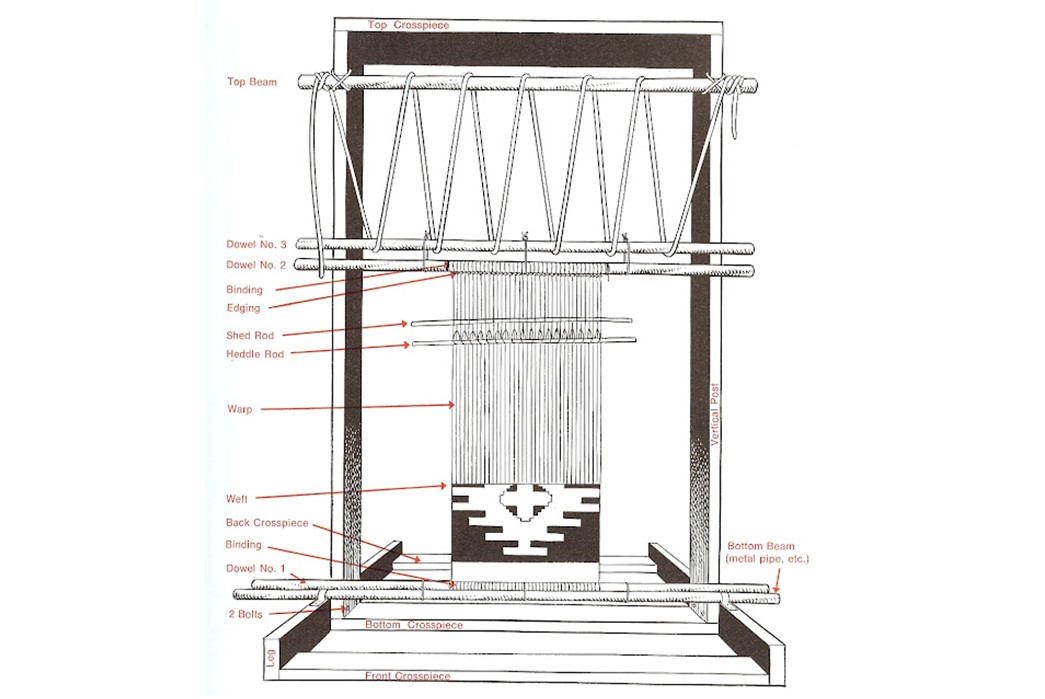

Navajo blankets were traditionally woven on primitive, hand-operated looms, pioneered in the area by the Pueblo people. The Puebloans—since the Spanish arrival in Southwest—had been faced with subjugation for more than a hundred years, and ultimately succeeded in expelling the Spanish rule in Santa Fe during the 1680 Pueblo Revolt. Following this event, many Puebloans sought refuge in Navajo homes, suggesting that this period was when they passed on the skill of weaving to the Navajo, although some sources suggest that Navajos had already picked up weaving half a century earlier.

The Puebloans brought with them Spanish sheep and introduced the Navajo to the vertical loom. Prior to the mid-seventeenth century, a backstrap loom, also called a belt loom, had been the norm for weaving. This loom, operated from sitting on the floor, was narrow and much smaller than the vertical loom, and couldn’t be used to weave a textile wider than 18 inches.

Pueblo woman operating a backstrap loom, also called a belt loom, in the nineteenth century. Image via Sarweb.

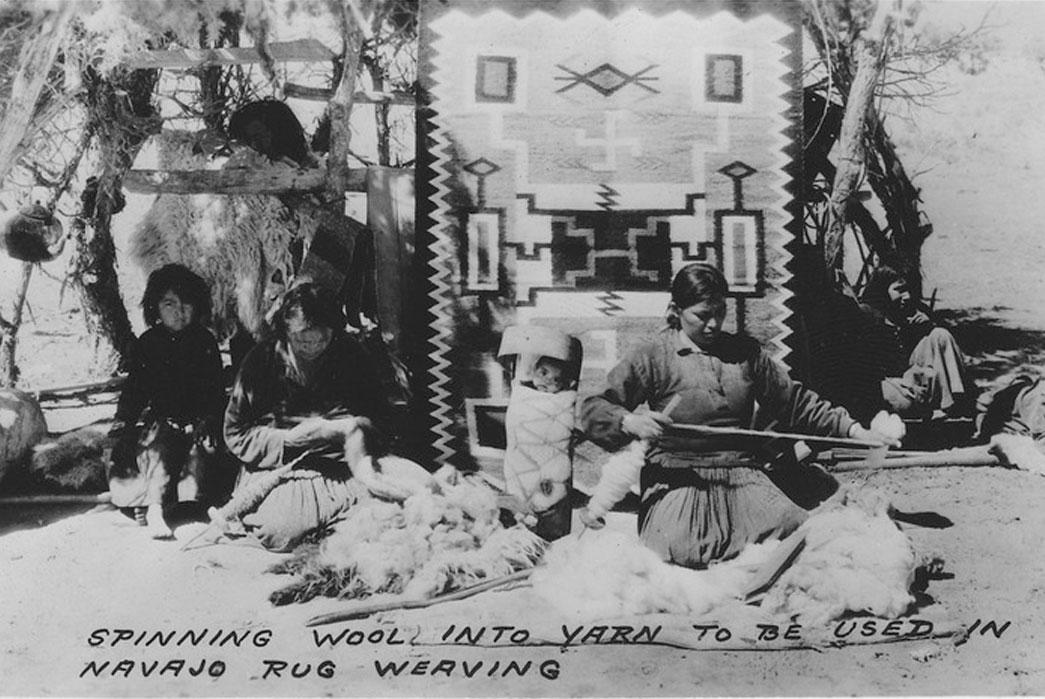

The Puebloans had been growing, spinning and weaving cotton long before the Spanish arrived in the sixteenth century, bringing with them Iberian-Churro sheep. The Churro sheep were famous for their long, smooth, silky staple fibers which were perfect for weaving. Through raids and trade, Navajos started herding sheep in the mid seventeenth century. From Iberian Churro sheep, the Navajo started breeding their own type of sheep, the Navajo-Churro.

Vertical loom as used by the Navajo in weaving blankets and rugs. Image via Art Quill.

Sheep and Early Colors

Traditional blankets were simple in design— early Pueblo blankets prominently featured banded stripe-patterns. The main colors of early blankets were typically grey, brown, tan, white or black, which was due to the natural color of the Churro sheep. Stripes were also colored with indigo, which could be obtained from indigofera shrubs imported from Mexico on pony caravans. The Navajo favored the color red, as it’s frequent in their weaving, but it was difficult to obtain red vegetable dyes in the Southwest.

Instead, red cloth was imported from England, as the English were accomplished at extracting carmine dye from the cochineal beetle. Brought over by the Spanish, who referred to the cloth as bayeta, the Navajo would unravel the yarn and weave the reds into their own blankets. In the mid-to-late nineteenth century, chemical dyes were invented and implemented for a greater color palette. The Navajos spun their own wool up until the 1860s when the US Army interfered.

Navajo-Churro sheep was bred by the Navajos from Iberian-Churro sheep brought to America by the Spanish in the 16th century. Image via Raising Sheep.

Bosque Redondo

Due to their traditions of nonconformity and penchant for raids, the Navajo, known to Americans as the lords of the desert, were feared and seen as a threat to the US government. In 1861 Major General James H. Carleton was assigned to solve the “Navajo problem”. He tasked Colonel Kit Carson who, through an elaborate assault and “scorched earth” military strategy (burning their land and killing their livestock), succeeded in forcing the Navajo from their land.

The deportation of the Navajo from their habitat in Northeastern Arizona took place from 1864-1866, when the US Army forced Navajos (and Apaches) to walk to a military camp, Fort Sumner, in the newly built Bosque Redondo Indian Reservation. This came to be known as “The Long Walk”, and the event is associated with much trauma for many Native Americans.

The Bosque Redondo experiment proved a massive failure, and in 1868 a peace treaty was signed, allowing the Navajo to return to their land. To get back on track, they were aided by the federal government, and part of this aid came in the form of new sheep—this time a French breed called Rambouillet . However, the wool of the Rambouillet was short and oily, and thus wasn’t suited for good quality-weaving. Although efforts were made to solve the problem, the wool was never quite the same after Bosque Redondo.

Navajo treaty singers around 1868 and The Treaty of Bosque Redondo. Image via Navajo People.

Early Use and Growing Popularity

Unlike many other “souvenirs” sold in the West, the Navajo blankets actually served a function in their own culture. The blankets were used in a wide variety of garments, including (but not limited to) dresses, saddle blankets, cloaks (called serapes), night covers, or even as a “door” at the entrance of their homes, called hogans, which were semi-permanent cabins traditionally made from wood, bark and mud.

The weaving of blankets is almost exclusively performed by women whilst the men were in charge of building the looms. A 1973 study conducted with Dine Community College has estimated that it takes an average of 345 hours, or over two weeks of active time, to make and sell a blanket:

- 45 hours to sheer the sheep

- 24 hours to spin the wool

- 60 hours to prep and dye wool

- 215 hours to weave

- 1 hour to sell

Types and Styles of Blankets

There are three major Navajo blanket forms worth knowing:

- Serape (shoulder blanket)

- Chief’s blanket

- Saddle blanket

A Serape is a shoulder’s blanket which is woven longer than it is wide. It’s woven vertically on the loom like all Navajo blankets, with the exception of the Chief’s blanket. The Chief’s is woven horizontally on the loom and is woven wider than it’s long. To see which way a blanket is woven, you can look at the direction of the warp cords.

The pattern design is also useful in distinguishing the two, as the Chief’s blanket will have a pattern which looks like it’s intended for horizontal display.

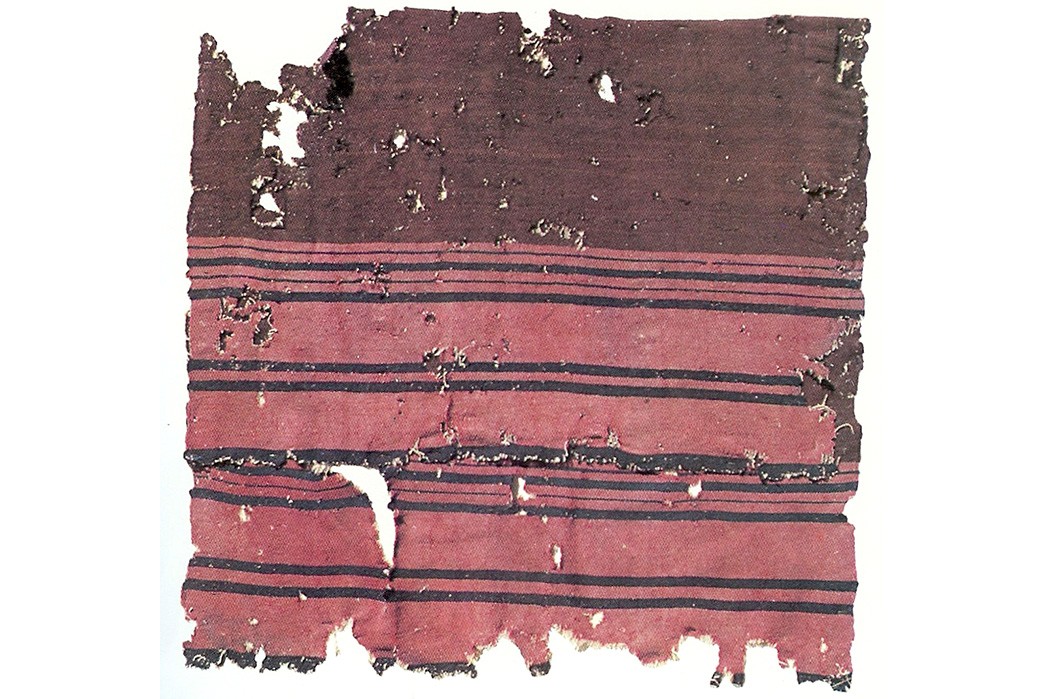

First phase Chief’s Blanket with black, indigo and bayeta (ravelled yarn) stripes on white background. Horizontally woven and horizontally displayed. Ca. 1840. Image via Donald Ellis Gallery.

Saddle blankets are smaller than the two aforementioned and square-ish, however double saddle blankets do exist and these are typically double the length for extra cushioning. Distinguishing the Serape from the Chief’s is not so easy if you’re not an expert on textile weaving. However, most (if not all) blankets are with collectors who know the distinction, so it shouldn’t be a problem.

Blankets by Era

Although Navajos themselves didn’t make use of the following classification, it can be a useful tool for collectors and historians in dating blankets to a certain period of time. The type of wool is a more precise dating tool, which is difficult to determine without having the blanket in your hands, and will usually require an expert. Please note that these dates are generalizations only, and will vary slightly depending on your source. A general consensus of the rough division of periods is as follows:

??-1804: Early Classic Period

Early Navajo blankets look similar to Pueblo blankets with banded horizontal stripes. The color palette is primarily composed of natural shades from sheep and native, natural dyes like indigo and ravelled yarn. These are often spun together in a mix of brown, tan, white, black, indigo and the occasional red.

1804-1880: Classic Period

The earliest confirmed Navajo weaving in existence, dated 1804, marks the beginning of the Classic Period. This was a sort of primetime for Navajo weaving. They spun their own wool from their own Navajo-Churro sheep and the quality was soft, warm and light, making them ideal for wearing. Because this was such an early period in regards to trade, the majority of the known blankets were Chief’s Blankets. Blankets from this period are known to be soft, tight and light in weight.

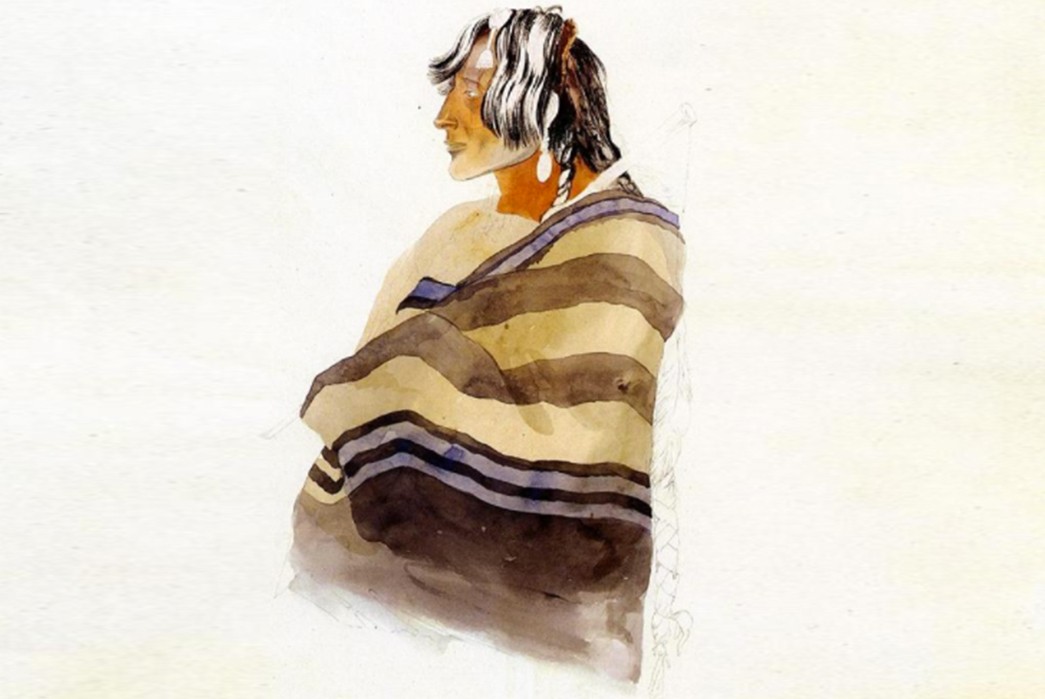

Kiasax: 1833 watercolour painting of a Piegan Blackfoot wearing a Chief’s blanket. Painting by Karl Bodmer. Image via Wiki Art.

Chief’s Blankets

Prized for their beauty and tight weave, well-to-do Spanish settlers or members of other tribes—like the Utes who commonly traded for Navajo blankets—would make use of the blankets in ceremonies. The blankets were expensive to make, both in time, effort and supplies, so only certain people could afford these blankets. That’s how these shoulder blankets came to be known as Chief’s Blankets.

The Navajo themselves didn’t make use of Chief’s in their tribes, but due to the status symbol it indicated, the blankets were given this name, and they’re some of the most collectible of all Navajo wovens. The first 50 years are scarcely represented, with an estimate of 50 surviving examples of the rarified piece. These major collectibles are priced at up to half a million dollars.

1868-1880: Transitional Period

The transitional period was due to the 1856 invention of aniline dyes in England, which reached the Southwest via the Santa Fe Railroad around 1865. The same year saw the import of three-ply dyed yarn from Germantown, Pennsylvania. Both happenings contributed to a wider variation of colors in the Navajo blankets. By 1875, Germantown was also making four-ply dyed yarn.

1880-1900: Eye Dazzler Period

In this period, weavers continue implementation of commercial yarn—like those in Germantown—which provided them with a wide range of colors. Bright, vivid colors were implemented in the blankets. The commercial yarn was expensive, and thus a stamp of quality as only the really accomplished weavers had commercial yarn available.

1890 Germantown Eye Dazzler. The name says it all. Image via Shiprock Trading Co.

Trading Post Era (Patterns/Schools of Thought)

Prior to the trading post era, the blankets were only intended for Navajos and for occasional trade with the Spanish and other Native American tribes. The blankets were sold at trading posts, the trade being the main source of income for the Navajos for many decades (as opposed to the agrarian culture of the Puebloans).

In the 1870s, the newly-chartered Santa Fe Railway started bringing Easterners to the Southwest. This would introduce Navajo blankets to a wider audience, and come to have a big impact on Navajo weaving in general. The Santa Fe Trail had opened up for trade already in 1822, and although the trail was rather dangerous, Karl Bodmer’s 1833 watercolor painting of a Piegan Blackfoot in Montana, wearing a Chief’s Blanket is a great indicator of how far Navajo weaving had spread.

Weavers in 1873 near Fort Defiance, New Mexico. Image Thomas O’Sullivan via Tom Clark.

But complications followed. The new demand for blankets and rugs meant that traders inadvertently contributed to deteriorating the standards, as traders started buying blankets by the pound. At first this was frustrating to the Navajos, so they started to deliberately overlook quality control such as scouring of the wool to increase the weight of the product and thus their income. Some even added clay to the bottom of the rugs.

This worked for a short while, but eventually no one wanted to buy the low-quality blankets and rugs. It should also be noted that the Rambouillet sheep the Navajos had been given by the US government following Bosque Redondo did not produce the same quality of wool as previously. Around the same time, Pendleton Woolen Mills introduced some new, cheaper wearing-blankets with Navajo motifs, which made it even harder to sell the Navajo originals.

One of the first trading posts in Southwest, Hubbell Trading Post, Ganado, Arizona. Photo around early 1900s. Image via Legends of America.

In the wake of this conflict, a more positive influence in design developed–quality control and marketing from American traders, an influence which was instrumental in saving the industry. The two most prominent names in this equation were John B. Moore of Crystal Trading Post and Lorenzo Hubbell of The Hubbell Trading Post (Ganado). Hubbell’s is one of the oldest trading posts, dating all the way back to 1883. These two assured quality control, including proper cleaning and scouring of the rugs.

They also implemented new marketing strategies. Pattern designs came to be influenced and associated with their given trading posts, and the two made sure that designs kept up with current buying trends. As kilims and Caucasus motifs were popular at the time, versions of these were implemented in the Navajo weaving.

Notice any similarities between this 100 year old Bakhitiari Kilim and Navajo rugs? The crosses in 20th century Navajo weaving most likely came from Caucasus weaving. Image via Triff.

Artists were commissioned to do rug pattern design, which the Navajos then modified with their own ideas. Moore even pioneered the use of mail order catalogs. Each had a different style, with Moore preferring natural hues and bright red accents, while Hubbell’s red aniline was his predominant color— a trait that came to be known as Ganado-style. Hubbell also introduced a black border to the rugs, and his style was generally more geometric compared to Moore’s. But both styles proved very popular.

Ganado rug from early 1900s. Notice the bright red background with geometric shapes as pioneered by Lorenzo Hubbell. Crosses probably inspired by Caucasus motifs. Image via Shiprock Trading Co.

Later Rug Periods

After 1890, cheap blankets created by Pendleton Woolen Mills could be imported via Santa Fe Railway. Bare in mind that these Navajo blankets were quite expensive at the time, selling at between $50 and $100 in 1860. But the Pendleton blankets only cost a fraction (around $3 dollars) of the original Navajo blankets and the demand for Navajo blankets quickly declined.

Late 1880s-1920: Early Rug Period

The import of cheap Pendleton blankets almost killed Navajo weaving, but luckily a different trend spawned in the aftermath of this incident. Navajo wovens grew popular for home decorations such as floor coverings, bed spreads, wall hangings, etc., and as such, a new market was created. Between 1890 and 1910 wool production more than doubled, while textile production escalated more than 800%. Purchases of manufactured yarn compensated for the deficit in wool production.

1920-1940s: Rug Revival Period

Demand for rugs had continued to grow into the 20th century. The US government made an effort to combat the poor quality wool of the French Rambouillet sheep they had introduced in the late nineteenth century. The Navajo Breeding Laboratory was established in New Mexico and eventually a better breed of sheep was developed. However the process came to a halt at the outset of World War II.

Blanket making in 1933. Image Bureau of Indian Affairs via Tom Clark.

1940s-present: Regional Rug Period

Following the example set by Hubbell and Moore in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, other prominent regional styles include:

- Two Grey Hills

- Teec Nos Pos

- Shiprock

1940s Yei weaving as related to the Shiprock region. Image via Shiprock Trading Co.

Weavers creating blankets at the Hubbel Trading Post in 1972. Image Environmental Protection Agency via Tom Clark.

Purveyors of Navajo Wovens and Availability

The oldest surviving Navajo rug is a so-called Massacre Cave blanket, dated to around 1804, when a group of Navajo people seeking refuge in the holy cave, Canyon de Chelley, were shot and killed by the Spanish. The blanket wasn’t retrieved from the cave until much later, as it was considered taboo for Navajos to enter the holy cave. And it wasn’t until an American trader, Sam Day, came along a hundred years later that the blankets were retrieved. He then sold the collectible blankets to museums around the US.

For a long time these vintage rugs and blankets predominantly belonged to the collections of anthropologists and historical museums as opposed to fine art collectors, but today there are quite a few specialist purveyors in the Southwestern Area, e.g. Shiprock Trading Co., a five-generation trading post in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Vintage Navajo rugs blankets are also popular amongst vintage Americana collectors and traders from all over the world, from US to Europe to Japan, and are commonly traded via eBay and Instagram, with no use of a physical store. In 2002, at the Tucson Antiques Roadshow, an owner of a First Phase Chief’s Blanket had it estimated at a price between $350,000 and $500,000 dollars.

One of the oldest surviving Navajo blankets, which is retrieved from Canyon de Chelly, also called Massacre Cave. Dated around 1804. Image via Art Quill.

The popularity and high regard of Navajo arts and crafts is a beautiful example of how a piece of primitive nomadic tribal culture have found its way into the homes of western civilization. Even given the historical context, the primitive lifestyle and hardships of the Navajo life, there’s very little to criticize. Oftentimes the historical context of an art piece can be just as enticing as the actual product itself.